The World as a Grand Search: A New Way of Understanding Everything

- Visarga H

- Jul 16, 2024

- 3 min read

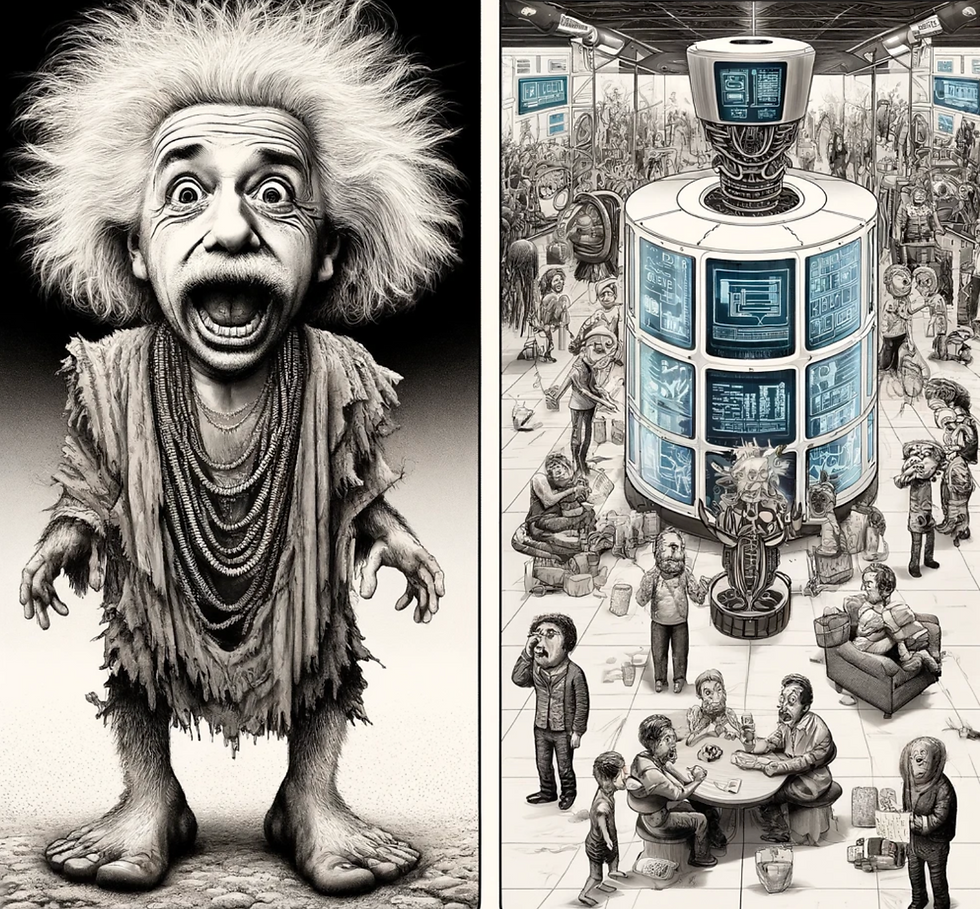

From the tiniest particles to the vastness of human culture, our universe seems to be engaged in a never-ending quest. Scientists and philosophers are starting to view this quest through the lens of "search" - not just the kind you do on Google, but a fundamental process that shapes everything around us.

Imagine you're playing a game of hide-and-seek. You're searching for your friends, exploring different hiding spots, and adapting your strategy based on what you find. Now, picture the entire universe playing a similar game, but on a much grander scale.

At the smallest level, atoms and molecules are constantly searching for stable arrangements. This atomic hide-and-seek gives us the rich diversity of materials we see in the world. Zoom out a bit, and we find living things searching for food, mates, and better ways to survive. This biological search, known as evolution, has produced the amazing variety of life on Earth.

Our brains, too, are incredible search engines. Every time you try to remember something or solve a problem, your mind is searching through a vast landscape of memories and ideas. Even creativity, often seen as a mysterious flash of inspiration, can be understood as an effective search through the space of ideas, filtered by trial in reality.

But what exactly do we mean by "search" in this context? It's more than just looking for something. Search, as a fundamental process, has several key characteristics:

It's compositional: Searches can combine to form more complex searches.

It's discrete: Search happens in distinct steps, even in seemingly smooth processes.

It's recursive: Searches can call upon themselves, creating nested structures.

It's social: Many searches involve collaboration or competition among multiple entities.

It uses language: Search requires some form of encoding to represent goals and actions.

It replicates and modifies information: Search processes can copy, alter, and build upon existing data.

These characteristics appear across various domains. In biology, DNA acts as a language for encoding genetic searches. In culture, ideas recombine and evolve through social interaction. In technology, algorithms perform nested searches to solve complex problems.

Viewing the world through the lens of search offers some exciting possibilities. Unlike abstract concepts such as consciousness or intelligence, search is inherently grounded in specific goals and environments. When we talk about a search process, we're always considering what is being sought (the goal) and where the search is taking place (the environment). This makes search a more concrete and observable phenomenon.

For instance, while "intelligence" can be a vague and debatable concept, we can more easily define and measure how effectively a system searches for solutions in a given problem space. Similarly, instead of grappling with the philosophical complexities of consciousness, we can examine how a system explores and responds to its internal states and external surroundings.

This grounding in goals and environments makes search more understandable and generalizable across different domains. We can apply similar principles to analyze searches happening in biological evolution, cultural innovation, or artificial intelligence algorithms. This universality allows us to draw insights from one field and apply them to others, potentially leading to new breakthroughs.

Moreover, the search paradigm shifts our focus from innate properties of agents to their interactions with their environments. This perspective helps us appreciate how what we often attribute to individual intelligence or creativity can arise from effective exploration of rich, complex environments.

By reframing phenomena in terms of search, we open up new avenues for research and practical applications. It suggests that improving search strategies – whether in problem-solving, learning, or creativity – could be a more fruitful approach than trying to enhance abstract notions of intelligence or consciousness.

Comments